Overview

The main learning goal of this tutorial is to enable historians and social scientists to gather Twitter data they can use as primary sources for research purposes or as teaching materials. We will first introduce the reader to the Twitter application programming interface (API) with particular attention to the limitations of the search API. We will then guide them through a first hashtag-based harvesting of tweets, for which we will use selected hashtags and provide examples of several that are relevant to historical memory. Finally, we will provide a basic analysis of the corpus of the collected tweets, by operating basic text mining operations and social network analysis.

Text mining can be defined as the process to derive information from large corpora of texts through computational operations of diverse nature. As such, it offers a range of methods and techniques to analyze content as data. On the other hand, it may also be interesting to analyze the structure of a Twitter dataset through the prism of social network analysis. Social network analysis (SNA) is “the process of investigating social structures through the use of networks and graph theory”. It sees social structures in terms of nodes (actors) and edges (relationships and interactions) that connect nodes. Frequently used in digital humanities or digital history, text mining and SNA are two kinds of analysis that can be applied to tweet datasets in social sciences and humanities (SSH). For instance, though tweets contain (short) texts, analysing a dataset of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or millions of tweets will require the use of text mining as it is not possible to read the whole dataset closely. Furthermore, tweets and their numerous metadata contain many kinds of interactions that can serve as the basis for social network analyses.

Tweets can be considered today and, more importantly, in the future as primary sources for historians. The two authors of this lesson, for instance, have used datasets of tweets to study the echoes of the Centenary of the First World War online within a memory studies framework and the Irish Decade of Commemorations from a feminist perspective.

There are various ways to collect tweet-related data; we propose here to use Netlytic, an online tool that does not require specific skills in programming. For this tutorial, you need to have both a Twitter and a Netlytic account.

Due to changes to the Twitter API access rules progressively applied in the first semester of 2023, it is no longer possible to collect tweets for free using the standard API. The Twitter data collection module on Netlytic has been decommissioned for this reason. Netlytic also recently announced that it will be integrated with Communalytic in 2024. However, the lesson is still of interest for several reasons:

- if you already have a dataset collected through Netlytic, then parts of the lesson are still valid

- the lesson demonstrates different ways to analyse social media data

- it draws attention to the problem of unequal access to research data in the digital age

- it showcases how we write history in the digital age

Overview of Netlytic

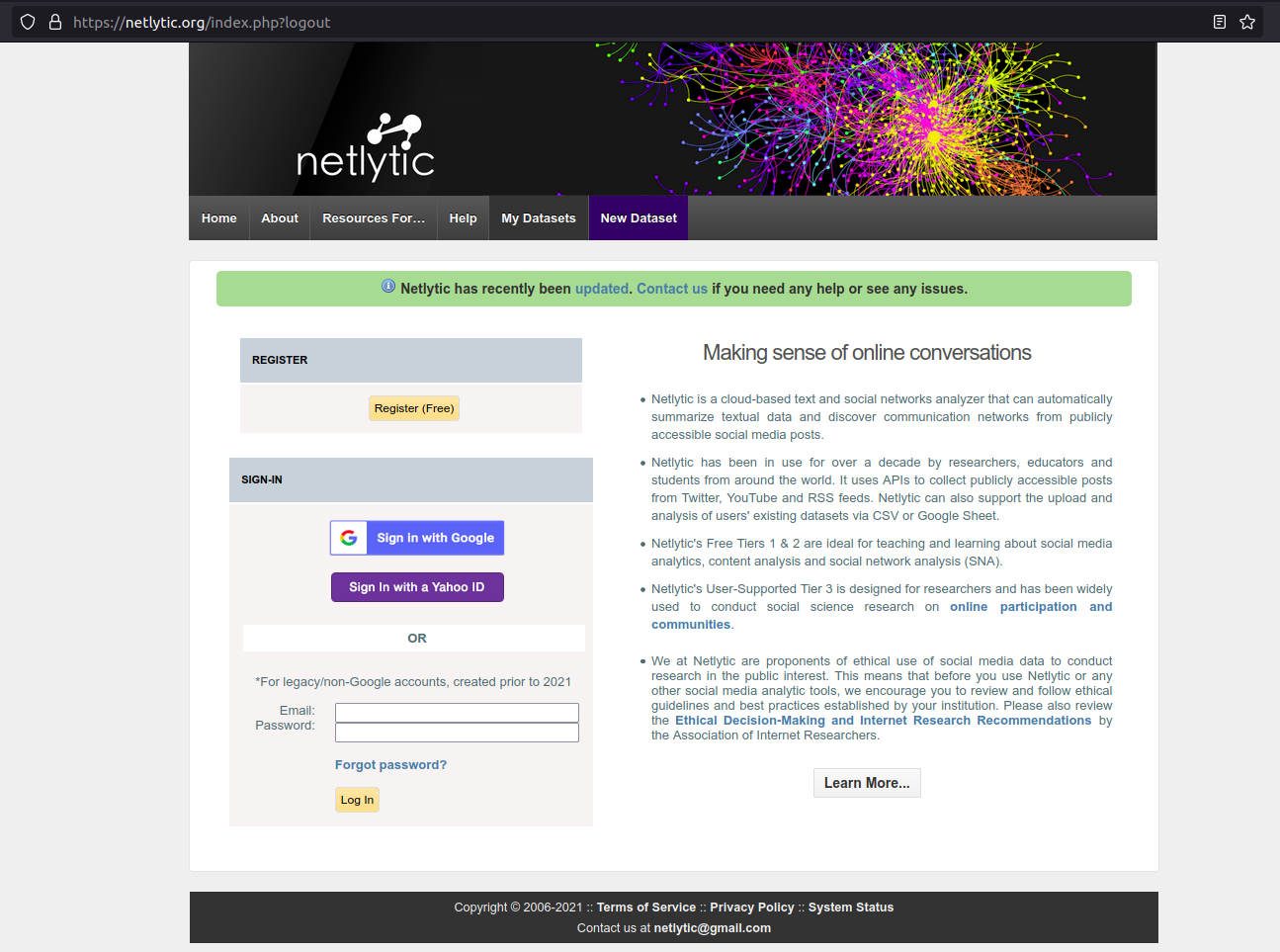

Netlytic is a cloud-based tool for collecting, visualising, and analyzing social media data from several platforms such as Twitter, YouTube, and Reddit. It has specifically been conceived for researchers who need not be familiar with a programming language or with the Twitter API. Netlytic offers three types of accounts (called “Tiers”), two of which are free of charge and offer the basic functionalities a user needs to create small projects. For larger projects, a third option is offered via subscription that allows users to create more and larger datasets. A free account is largely sufficient to follow this tutorial.

Once you have an account, you can select the data to collect either using hashtags (#keyword) or simple keywords (not preceded by hashtags), or even replies/mentions (@username), and other custom-built filters. To collect the data, the current version of Netlytic uses the Twitter REST API v1.1. Once collected, the datasets are stored online by default, so users should consider whether this complies with their university’s ethical guidelines for social media research. The number of tweets and datasets a user can store at any one time is limited. However, datasets can be downloaded as CSV files for working offline with other programs and freeing up space for more data collection. After collecting the data, users can also carry out network analysis and basic text analysis. Furthermore, existing datasets can also be uploaded for analysis.

Setting the scene: what is the Twitter API and how does it work?

An Application Programming Interface (API) is “a way for two or more computer programs to communicate with each other. More precisely, it is an interface that allows one piece of software to offer a service to other pieces of software. An API is usually documented, so that developpers can implement it in their programs. The services accessible through an API can be of different natures. In the case of social media, like buttons from Facebook that you can see on many websites are using the Facebook’s API. In this lesson, we are more interested in another kind of service that can be accessible through an API: data and metadata.

In its API, Twitter offers five groups of “endpoints”: “accounts and users”, “tweets and replies”, “direct messages”, “ads” and “publisher tools”. An endpoint corresponds with a specific type of information you can get or send. The “tweets and replies” group is the one that is of interest to us here: it makes public tweets and replies available to developers and allow to post tweets through the API. If you wish more information about the other groups of endpoints, please, read this post.

Twitter’s API belongs to a wider family of API called REST. If you wish to know more about REST APIs, we advise you to read: What is a REST API. Also note that there are currently two versions of Twitter’s APIs, version 1.1 and version 2. If the APIv2 will in the future be the only one remaining, the APIv1.1 is not yet deprecated. As Netlytic is for now using the Twitter API v1.1, we will focus here on this version. If you wish to know more about the difference between those two API versions, please read this page.

In the “tweets and replies” group, there are several ways to search and collect tweets and replies. We will detail two of them here: the streaming API and the search API. The streaming API allows developers to collect tweets that are currently being published. This streaming API does not provide access to historical tweets, but allows the collection of up to 1% of the firehose (i.e. all tweets being published in real-time). The Search API allows the searching of historical tweets up to 7 days in the past, and up to 450 requests per 15 minutes. For a more precise overview of the standard search API, please read this page. We will be using the standard Search API for this lesson.

There are many limitations to the use of the standard search API. We have already mentioned the 7-day limit on searching historical tweets and the rate limits. We should also add that there is no guarantee of acquiring all matching tweets through the standard (free) API. Any tweets sent by private Twitter accounts will also not be included.

Your first harvest of tweets

After creating an account on Netlytic, once you are connected, please go to the “My account” bar in the main menu and link your Netlytic account to your Twitter account. Then click on the “Sign in with Twitter” button and follow the instructions. This is a mandatory step. If you do not authorize your Netlytic account to access your Twitter account, you will not be able to collect any Twitter data.

Before you begin to collect data, you will need to choose a topic and find your hashtags. To choose a hashtag or a simple keyword, please go the “How to choose your hashtag?” section below. Once you know what you are looking for, click on “New Dataset” and choose the “Twitter” tab.

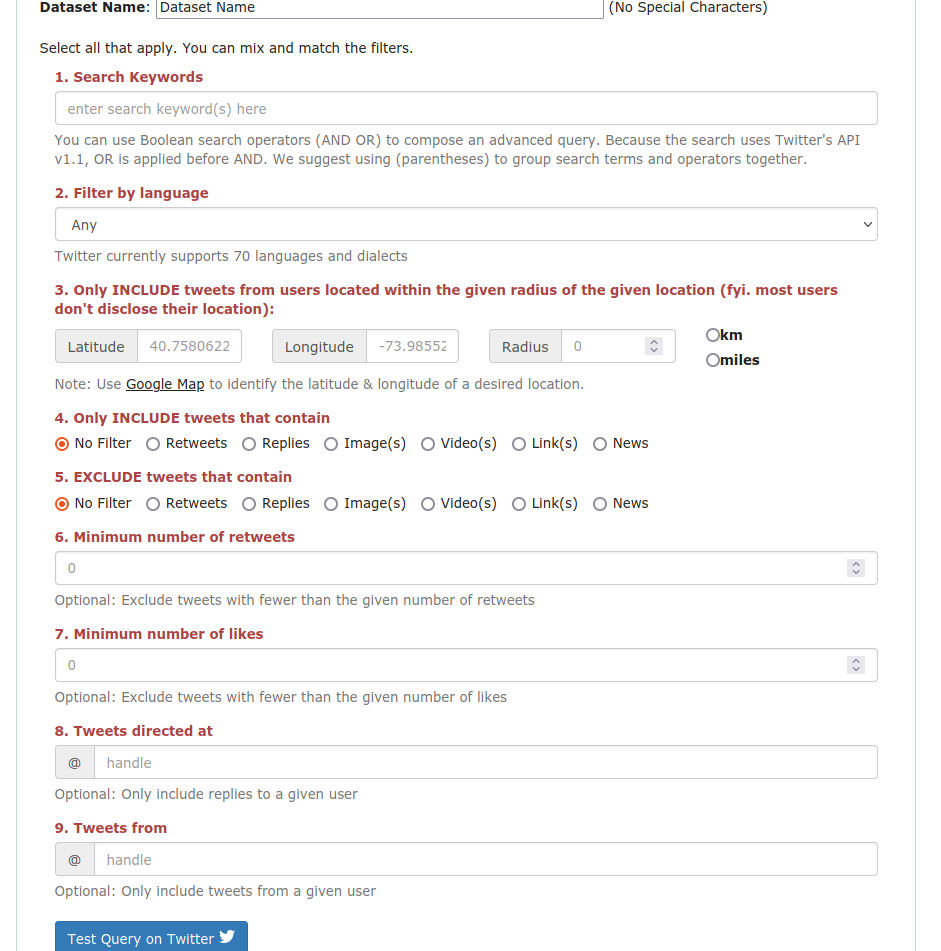

As you see, you will be asked to:

- Choose a name for your dataset

- Search keywords

- Define filters (language, geographic limitations, include / exclude / number of retweets / number of likes / to / from)

You will have to fill in a form to register all this information.

Caution: the filters may not be perfect. For example, when you set the language filter to “French” a dataset will be returned with a very large majority of tweets in French, but it will also harvest a minority of tweets in other languages. Similarly, because most users do not disclose their location, the geolocation filter may greatly reduce the number of tweets you can collect. You can try the filters by going to the Twitter advanced search interface.

We will not use those filters, but depending on your research, they might be of great use. For instance, if you are studying the interactions between a museum and its audience, you might want to limit your query to tweets published by the museum’s accounts or the replies to those tweets (using one of the @mention filters).

Choose your hashtag and build your dataset

To build your dataset, you may want to study what is called a trending topic. Trending topics are theoretically a way to understand what people are discussing on Twitter, but the way they are defined has evolved and became more complex over the years, depending on the context: for instance, if you are consulting Twitter in the UK, you might see trending topics that are closely linked to this country. To find the most discussed issues, you can explore dedicated websites, such as Trends Twitter, or the trending hashtags directly via Twitter’s interface. For example, you can go to Twitter, use the Explore tab of the menu to search for hashtags. Tweets that appear in the search results might contain other hashtags beyond your initial search: you can then follow the chain of hashtag links to collect the most relevant ones for your query. This is known as the “snowballing” technique. Of course, you may already have a defined object of interest and look for specific keywords independently of the trending topics.

You should also consider the expected size of your corpus of tweets. How big should your corpus be? Or, otherwise stated, how many tweets do you need for your research to produce reliable results? The answer will depend on many factors such as your research and topic (what you want to study, how you want to study it), the number of tweets that were produced around your chosen topic, and technical limitations (the tool you are using to collect the tweets, Twitter API’s limitations, etc). It is not a question that we can answer within this lesson, as each case is special.

Some important points to understand to help you maximise your query:

- You can create Boolean queries using keyword combinations, AND and OR statements, exact matches by “putting statements inside double quotes”, and grouping search terms and operators inside parentheses to broaden the corpus. For example, if I want to find tweets about the commemoration of the women involved in the 1916 Easter rebellion in Ireland, “women AND centenary” would not be specific enough, and we would request (women centenary AND (1916 OR “Easter Rising”))…

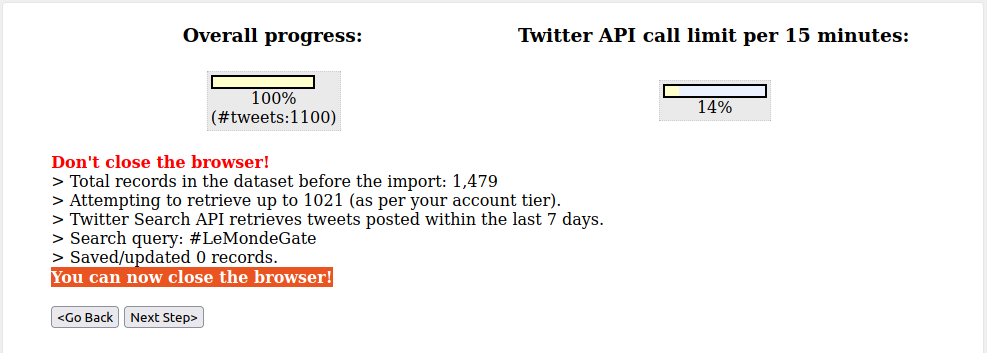

- Depending on the topic you work on, it may not suffice to follow a small set of hashtags to build your corpus. Topics like #Brexit or #Covid19 produce millions of tweets a day; however, with some exceptions, commemorations generate far less tweets. If your preferred topic is of the kind to produce a very small corpus, which might hinder a meaningful analysis, you may need to use keywords in addition to hashtags. This type of query can become complex, but still you can test it using the Twitter search bar to make sure it returns the expected results before implementing them in Netlytic. To do this, use the “Test Query” on Twitter button at the bottom of the page while you are connected to Netlytic’s interface (see note below). Although this will direct you towards the Twitter search interface, which we advise you to use, however it will not create your dataset. To do this, you need to click on the “Import” button. A new page will then be loaded: be careful to not close your window and wait for the “You can now close the browser!” message.

- You can build your corpus over a few days if necessary. You can queue your request and analyses by enabling Netlytic to continue collecting tweets every 15 minutes for a specified number of days (up to one month). You may, for example, need to anticipate a major/annual commemoration or historic event. Some examples of annual “memorial” hashtags include: #WW1 #LestWeForget #BloomsDay #ArmisticeDay.

- Netlytic allows you to apply filters to search queries for tailored results, e.g. limiting to tweets above a certain number of likes, tweets that are from or in-reply-to a specified @user, or tweets that include media (images, links, videos, polls), filtering by language etc.

- If there are no tweets that match your query, you will receive an error message.

Congratulations! You now have your first Twitter dataset ready and can analyze it in various ways. To do this, click on “Next Step”.

Text analysis

Text analysis is one of the basic operations of analysis you can apply to a corpus of tweets. Below we present how you can use the functionalities for text analysis offered by Netlytic. However, it is possible to export your data and analyze them with any method and tool that you prefer - we mention some at the end of this section.

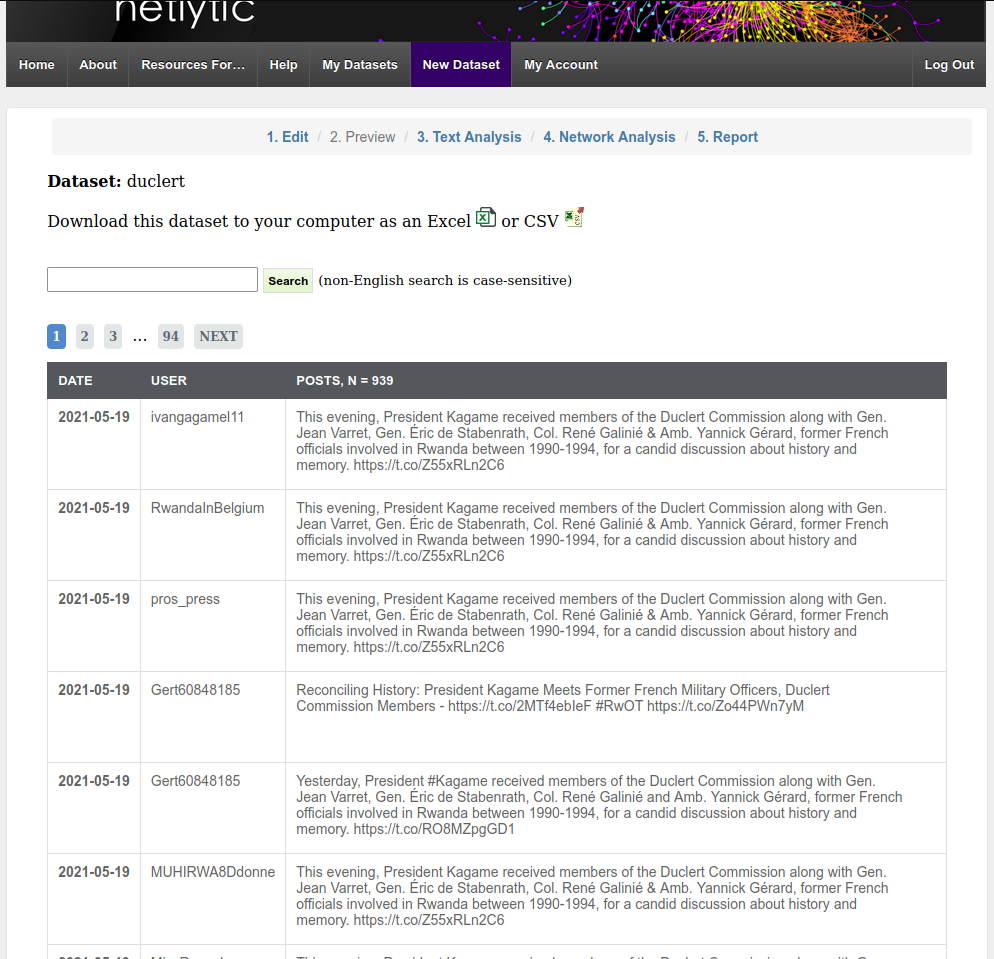

Once you have your dataset, as shown in the previous step, go to “Preview” where you can browse a table of the tweets that you have collected; a search bar is available for you at the top if necessary. At this point, you can download an Excel or CSV file of your Tweets, if you wish. We strongly recommend you do so, to preserve your data and be able to reuse them in your future research activities.

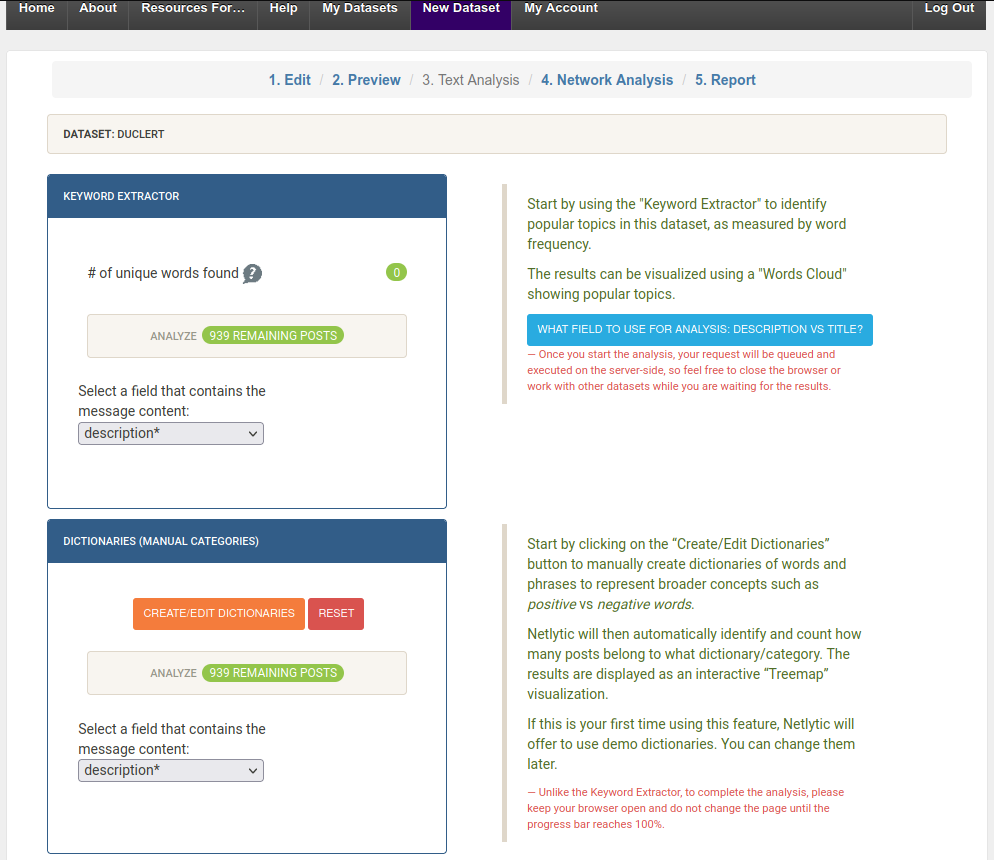

Next, let’s see how you can visualize the words that are the most frequent in your corpus. If you click on “Text Analysis” in the tab, you will see two options: “Keyword Extractor” and “Dictionaries”. At this point, we are interested in the first one, which allows you to obtain a visual representation of your textual data based on quantitative analysis. In the Keyword Extractor, make sure the “field” is set to “description” and then click “Analyze” to generate a word cloud of the top terms and hashtags in your dataset - this will be queued in the server and you may need to wait a few moments. Then click on “Visualize” to view and explore the word cloud. You may also download these data as a CSV file, if you wish - and again, we strongly recommend you download and preserve any data you use for your analysis.

But you can do more than this. For example, you can also click on a keyword or hashtag to inspect it in context (i.e. where the term appears in the tweets). Or you can use the functionality of “Dictionaries” to create groups of tweets that are linked to specific concepts. Netlytic has preloaded dictionaries based on sets of adjectives, that will allow you to categorize tweets. Those spatial and temporal categories include: size, shape, touch, time, quantity, sound, taste, feelings (good), feelings (bad), condition, and appearance. You can also create your own categories as well, if your research requires it.

You may also visualize the dictionaries of your corpus as a “tree graph” - which is another way to circulate within the information contained in your corpus - or click on the boxes to dig deeper into the categories, and see the different keywords in context. You can explore more in depth in what ways dictionaries can be used for analyzing social media data in an article that examines toxic discourse in YouTube commentaries.

You have learnt a lot of things, now let’s take some time to reflect. Netlytic has allowed you to generate and explore a word cloud based on your corpus, but in what ways precisely did this help you to understand and analyze your data? How useful, or not, has this been for your research? To help you think through these questions, you can read this article that discusses the limits of word clouds. You can even try to use other tools and compare the visualizations that you get: Voyant Tools is one option, but you can browse the Text Analysis Portal for Research (TAPOR) to pick your preferred tool. Note that using different tools may require you to do some data cleaning - for instance, you might observe that Twitter handles are appearing in the word cloud and this is not of great interest - or special formating. A quite comprehensive article on data cleaning can be found on Wikipedia. You can also discuss your experience with your colleagues or classmates or even a community of users.

Network analysis

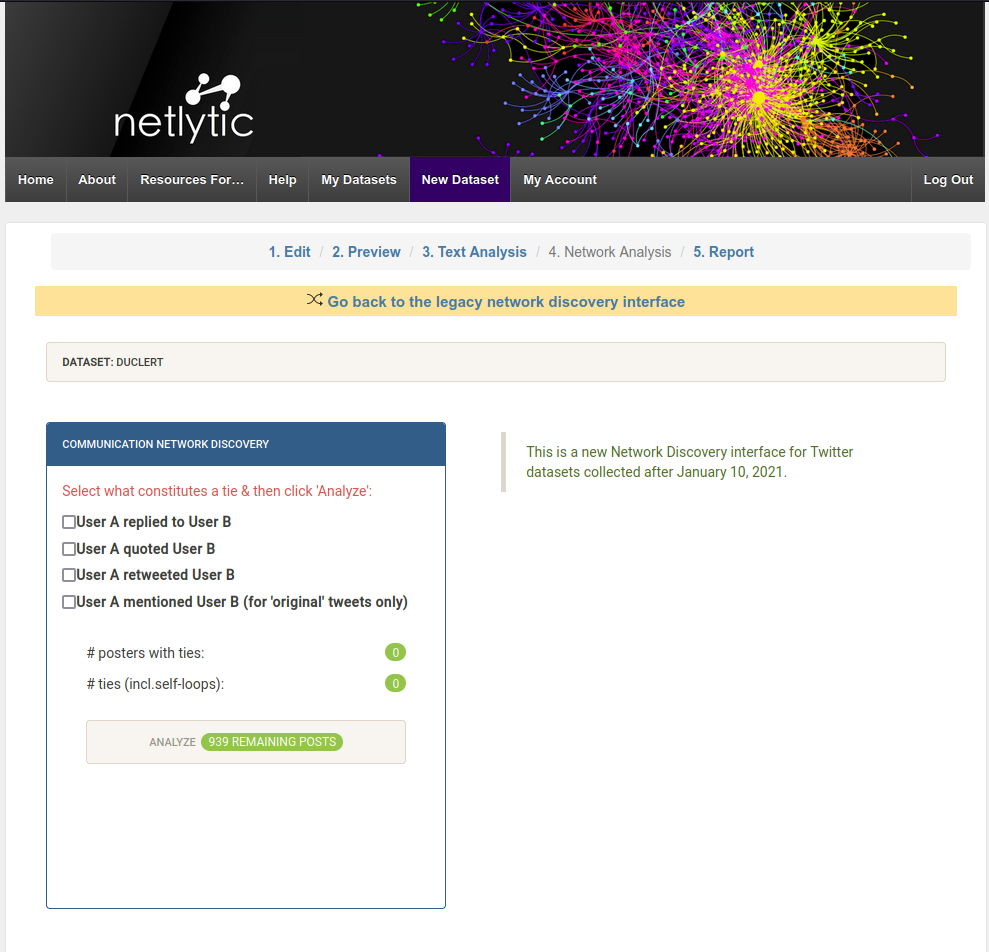

Network analysis involves a second kind of analytical operation that one can apply to a social media data corpus. If you are not familiar with this domain, Marten Duering’s lesson on data extraction and network visualization of historical sources offers a nice introduction for beginners. Once you have your dataset, click on the “Network Analysis” tab and you will see several options for different types of what, in Netlytic, is called “ties”. The ties represent interactions between Twitter accounts, which can be of different types: retweeting (quoting another account’s tweet with no modification), quoting (quoting another account’s tweet with a comment), mentioning (publishing a tweet with another account’s handle in it), replying (using the “reply” functionality: your tweet will then appear below the original tweet and start or continue a conversation). The Twitter accounts are the nodes of the network you wish to inspect and the ties of different types are the relationships that connect these nodes between them.

Choose the type of interaction you want to examine and click on “Analyze”. You will first obtain the number of Twitter accounts who are tied by retweets or tied in self-loops. A self-loop represents users (Twitter accounts) replying, quoting or retweeting themselves. Next click on “Visualize” and a pop-out will appear of a retweet network visualisation.

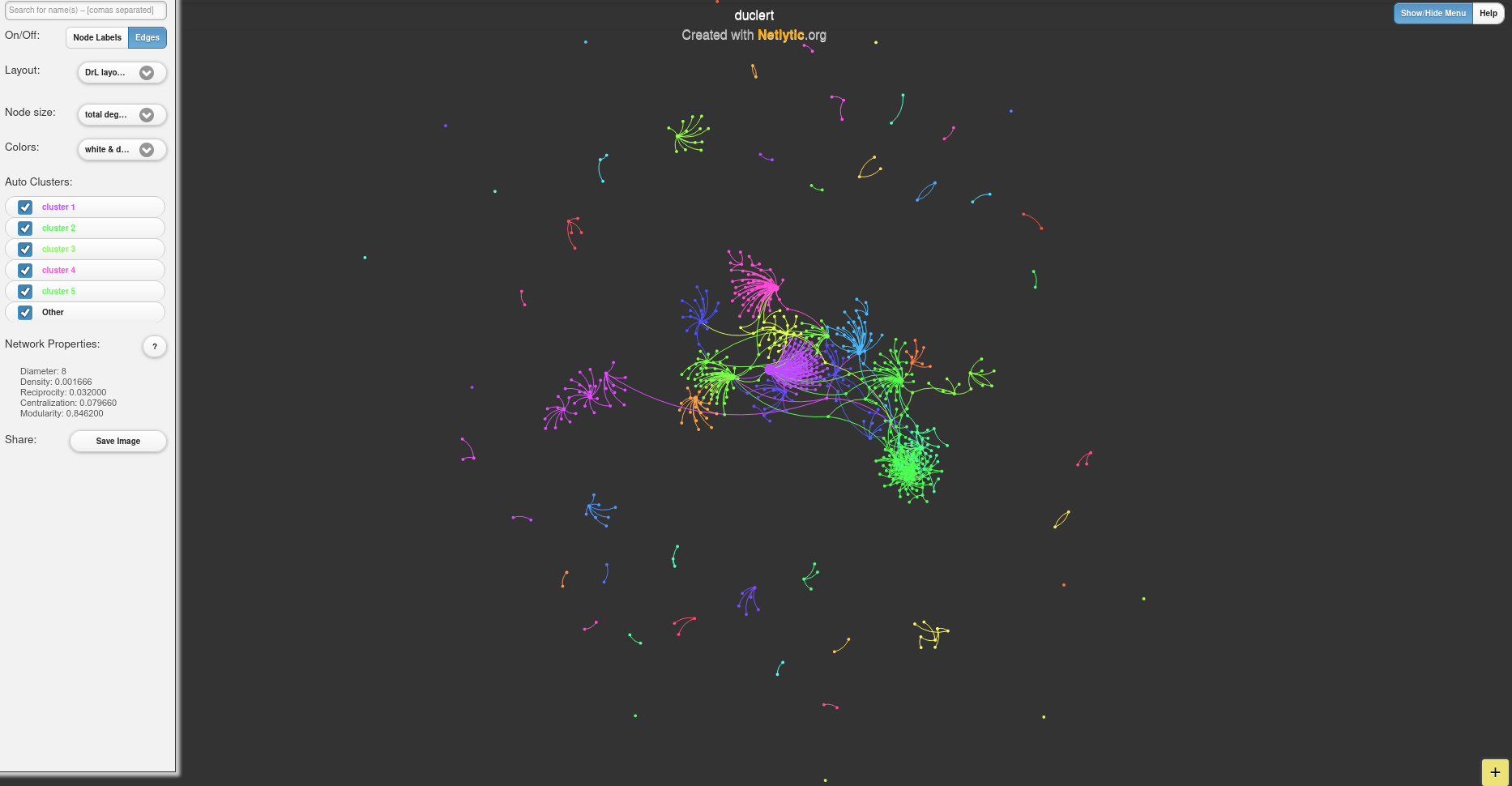

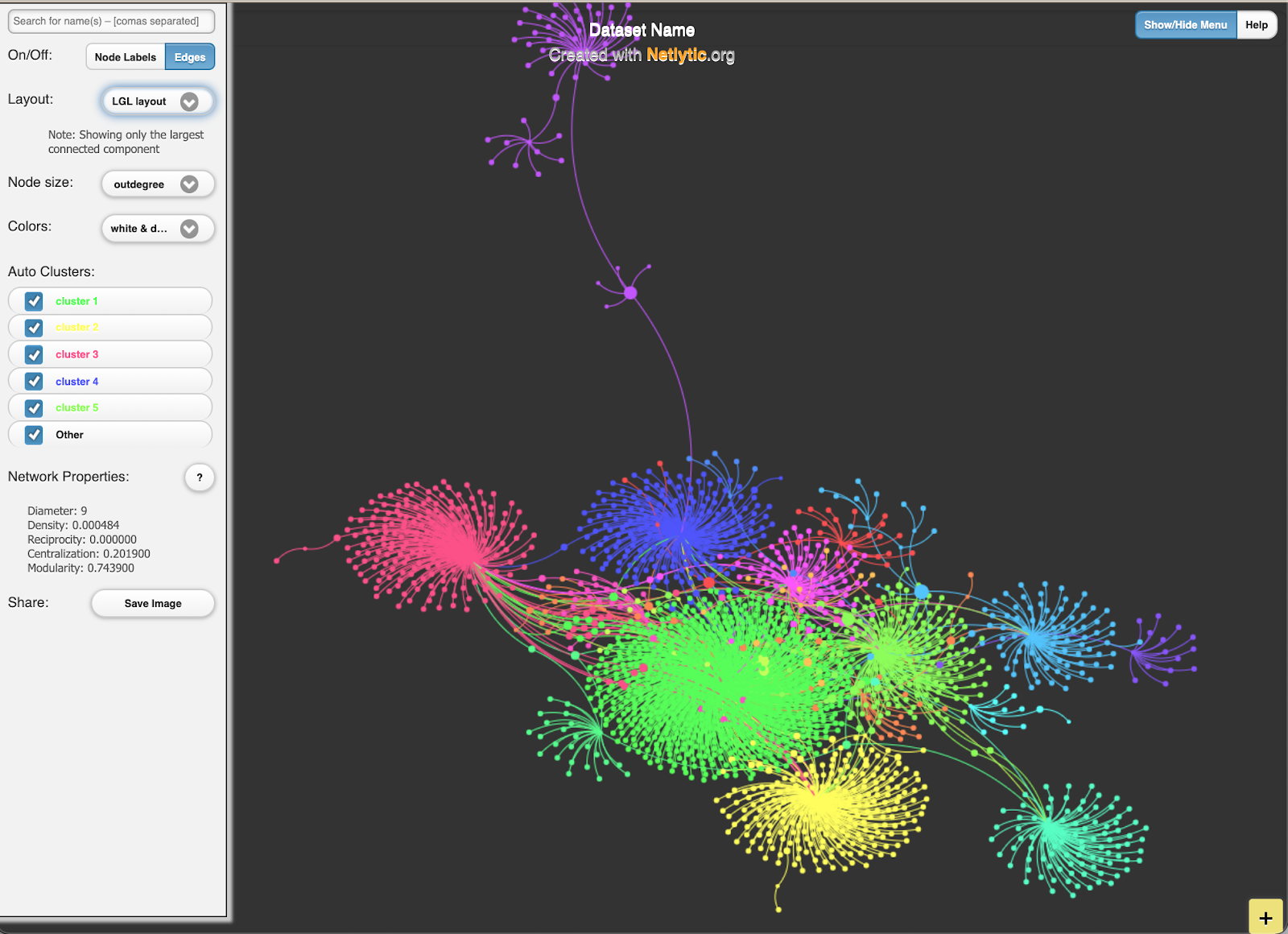

There are here two important things to mention. First, the nodes - the Twitter accounts - are grouped in clusters which means these accounts share some form of similarity. These clusters are calculated by an algorithm that detects what we call communities of users. Second, you have the possibility to choose a layout for the visualisation of the network you study. A layout is a way to display the nodes (Twitter accounts) and the “edges”, which is another way of saying ties or links. A layout allows you to see patterns in the structure of your network. Layouts are based on algorithms, which is why there are different possible layouts. The best layout is the one that fits your dataset and your research purpose, there are no “good” or “bad” layouts per se.

You can use your visualisation to experiment with different layouts and see what kind of visualisations they produce for your network. You can also take a closer look at what constitutes your network. For example, you can hover over the nodes to check the usernames, if you need to, and you can even uncheck “Edges” (the ties between the nodes) to focus on nodes only. Furthermore, you can explore the metrics that define in what ways the network’s nodes are central or not and make these metrics visible by playing with the node sizes. If you wish to focus on different parts of your network, you can uncheck “Layers”. This will help you to focus on larger nodes, i.e. have a less detailed but clearer view of your network. Larger nodes represent Twitter accounts with more interactions with other accounts. All these are different ways of representing the data - but remember, visualisations are interpretations, they are not raw data. If you are happy with the results, you can also save and export your visualisation to integrate it in a future report/presentation.

How can network visualizations be useful for historians? There is a vast bibliography but this is not the object of the current tutorial. What is useful to remember, however, is that you need to fix and focus on a research objective that is part of a historical question. You may benefit from Martin Grandjean’s general introduction to social networks analysis in history, which will also help you to learn more about network metrics and structure such as centrality degrees or communities. These are metrics that help analyze social media, and specifically tweets, networks, in order to identify dominant voices (nodes / Twitter account) in the network (official, news media, themed accounts, cultural institutions, individual influencers…).

As in the previous type of analysis, you can download your network’s data as well and do further analyses with Gephi software or your preferred tool of social network analysis. To learn how to use Gephi, you can follow Martin Grandjean’s tutorial.

Reading suggestions

For more case studies and tutorials using Netlytic see: https://netlytic.org/home/?page_id=11204

LSE Blog - Using Twitter as a Data Source

Ahmed, Wasim, Peter A. Bath, and Gianluca Demartini. 2017. “Using Twitter as a Data Source: An Overview of Ethical, Legal, and Methodological Challenges.” In The Ethics of Online Research (Advances in Research Ethics and Integrity, vol. 2), edited by Bath Peter A. and Kandy Woodfield, 79–107. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2398-601820180000002004.

Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. 2012. “Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon.” Information Communication and Society 15, no. 5: 662–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Bruns, Axel. 2019. After the “APIcalypse’: social media platforms and their fight against critical scholarly research.” Information Communication and Society 22(11), 1544–1566. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1637447

Clavert, Frederic. 2018. “Commémorations, Scandale et Circulation de l’information : Le Centenaire de La Bataille de Verdun Sur Twitter.” French Journal for Media Research 10, (special issue: Le Web 2.0 : lieux de perception des transformations des sociétés). http://orbilu.uni.lu/handle/10993/36120.

Gruzd, Anatoliy, and Philip Mai. 2020. “Going viral: How a single tweet spawned a COVID-19 conspiracy theory on Twitter.” In Big Data & Society 7, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720938405.

Janetzko, Dietmar. 2016. “The Role of APIs in Data Sampling from Social Media.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase, 146–60. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473983847.

Rantasila, Anna, Anu Sirola, Arto Kekkonen, Katja Valaskivi, and Risto Kunelius. 2018. “#fukushima Five Years On: A Multimethod Analysis of Twitter on the Anniversary of the Nuclear Disaster.” International Journal Of Communication 12: 928–49.

Rockwell, Geoffrey, and Stéfan Sinclair. 2016. Hermeneutica: Computer-Assisted Interpretation in the Humanities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Rogers, Richard. 2019. Doing Digital Methods. London: SAGE Publications.

Smyth, Hannah and Diego Ramírez Echavarría. 2021. “Twitter and feminist commemoration of the 1916 Easter Rising.” Journal of Digital History, 1, no.1. https://journalofdigitalhistory.org/en/article/SLCj9T3MsrEk

Thoreau, Henry David. 2016. “Walking.” In The Making of the American Essay, edited by John D’Agata, 167–95. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press.